When the Villagers Take on the Gatekeepers

Pandas or heart disease? Or perhaps today I’d hit the jackpot and be paired with some kind of child neglect charity? I was working for a telephone fundraising company, and the pay-packet lived and died with how much sympathy the charity you button-bashed for could squeeze out of people.

Each shift, I’d need time to myself before the harrowing seven hours of asking people for money. This meant sitting in hateful silence, smoking Mayfair Lights in a stairwell, making intense but understanding eye contact with people in the same boat. All you hoped was that you were assigned a desk where you could sit with your screen facing the wall and hang up on calls the entire shift.

My boss swung violently from best mate to tyrant. One day she’d be oversharing about her divorce and how she needed to go shopping at lunch to replace the spunk-stained skirt she had on from a one-night stand. The next she was master of the ominous *click* on the line. The click where you knew someone was listening to the call, making sure you were sticking to the script. Even if the old dear on the other end was already in debt to a motorised-armchair salesman.

I stayed there far too long with impressively low “sales”. My primary skill was being able to talk on the phone with people lonelier than me. One time, I cold-called a charming guy who pleaded with me that I couldn’t set up a direct-debit because he was a struggling musician. I committed his name to memory and years later would run into him at an industry party. He’d become a moderately successful songwriter so I cornered him, slurring, to tell this story five times throughout the night.

Back then I did anything to keep my head above water and it felt exciting. The freedom of not caring about my job. The unbridled joy of selling t-shirts I'd made to people in the toilets of Fabric. The stream of projects I’d start with no intention of finishing, I just wanted to do them.

Now, that fated “hustle” is not so endearing. You will inevitably reach an age where friends start to ask you what you think about settling down. About marriage and starting a family. About what mortgage schemes work, what pension you should have. Which is quite unsettling when you feel like you've never had your feet on solid ground.

Every part of talking about money is excruciating to me. The selling yourself, the negotiating, the lack of shame. But the worst part is that unshakeable deception that money is a reliable barometer of talent. Which is odd when you’re in a line of work that simultaneously romanticises being broke.

That said, I’ve never had a problem getting cash when it comes down to the wire. The idea, however, that it is an ‘energy’ that magically ‘flows’ towards you with the right mindset is lost on me. Money has always flowed distinctly away from my bank account and success I’ve only ever been on the periphery of.

When I found myself out of work yet again I wanted to scream at the inertia of the industry. How had the rates not changed in over five years? Why was working for exposure still a thing? So much so that I applied for medical trials “as a joke” knowing that it was also as a “totally serious financial endeavour.” I still had this conceit that if I shirk a ‘normal’ job for as long as possible, somehow, everything would work out.

So I signed up for Flu Camp. A haven for students and professional wasters where you sit in a quarantined ward playing The Sims and are given microdoses of the flu for money. The only thing between me and three thousand pounds was a few simple blood tests. I started to plan what I’d do in flu isolation as the nurse checked my veins. Maybe I’d write a screenplay about a downtrodden young woman fired from a job. I could invite all my old co-workers and exes to the grand opening of the film and yell abuse at them with a Merlot-stained mouth. Then the nurse checked my other arm. And then my hand. Then back to the first arm. Prodding me with a needle before wincing and giving up.

Every time she circled around the other candidates, who were seemingly pissing blood, I’d furiously pump my hand hoping my veins would start being useful for once in their stupid lives. In the end, I had to stomp back to the tube station defeated. I could not get past the first stage of offering my body to medical science. When I die the organ donor list will be like “Nah, we’re good.”

But then my settlement was agreed.

It came under the condition of a gag which I signed the next day. The legalese was worded in such a way that I was terrified of the repercussions. The back-and-forth had been so barbaric that I wasn’t convinced they wouldn’t fabricate or pull strings to ensure my career was suitably dead in the water if I spoke out.

In the end, I received just shy of twenty thousand pounds. Exactly the salary I’d started on as an editor, to babysit a publication with no paid holiday and no commissioning budget. It was a recipe for disaster from the start. I invoiced every month in the hope they’d pay on time, which they didn’t, and was responsible for my own taxes, which I wasn’t. Like everyone else I knew, I didn’t do my taxes because a) I had no clue how to and b) the leftover amount to live on in London would mean surviving off my own toenail clippings.

The longer I stayed at the company, the more profound the unfairness in salaries and more pronounced my lack of financial home-training became. Every time I pushed them on pay they'd edge me further out to pasture. I remember the last office drinks I went to, select employees had been invited to a private party which gave me very strong Jim Jones in the jungle vibes. During the lock-in, I took the opportunity to saunter up to the Scotch-soaked CEO and asked him, jaw-clenched and very close to his face, when I could expect a better fucking wage. He let out a belly laugh, before explaining how I was aggressive, unpredictable, and not palatable to anyone with money and never would be. That stuck in my throat. I am those things but I did not know you couldn't just be good, you had to worry about being likable to some prick with a cheque book as well.

In the same month I had another raise turned down, the accounts department accidentally sent me a bank transfer for an executive’s ‘shoot expenses’. It was a quarter of my yearly salary. Which, if you knew the tantrums and undermining you were subject to, to deliver a fully-formed project for the cost of a gram it was...surprising.

When the settlement finally hit my account I got out of this world wasted but it didn’t feel like a win. Distant acquaintances got in touch like “oop, drinks on you then!” without knowing most of it had already disappeared on catastrophic back taxes and credit card debt.

By the time my nest egg was nearing nil, details of the case were reduced to a paragraph in an article and relayed on a men’s rights activist forum. Overnight, I had a slew of messages calling me a money-grabbing whore. One email said “you aren’t attractive enough for a sexual harassment lawsuit,” which is just, y’know, patently untrue. But it did make me think about what a paltry sum of money it was for the grief it came with.

Everything that was yanked kicking and screaming into the mess — sex, race, harassment, drugs, bullying — were secondary to the reason it all got so ugly: asking to be paid fairly. It has been four years and I still can't get my head around why this was a wacky concept.

Nobody can prepare you for the shock of losing your income suddenly. The ravine you have to cross to safety is so far removed from bowing out of a job gracefully.

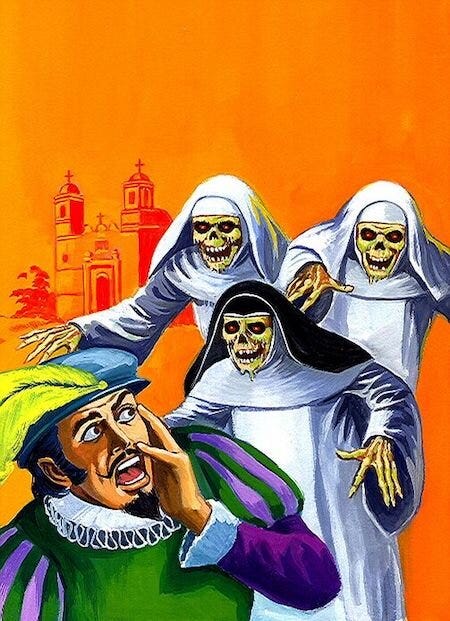

But I do have a perverse interest in the idea of entire industries being burnt to the ground and rebuilt. The schadenfreude of gatekeepers finally being overwhelmed by angry villagers might be just the tonic.