That One Time a 15-Year-Old Called Me a Pussy'ole

There are good and there are bad teachers, just as there are good and bad journalists. But the difference is everyone in journalism for some reason buys into the idea that what they do is inherently noble. That they are permanent and important and society as we know it would collapse without them. However, it’s also an industry so comically overrun by the expensively-educated that the assertion every article farted out speaks up for the little people is surreal.

I’d been toying with teaching as an escape route for some time. Something that would make me feel like I was moving forward rather than weighed down by the chip on my shoulder. And, arrogantly, I thought I’d still be able to write on the side. I could come home from a day of students applauding me at the end of every lesson and bash out a best-selling novel in the evenings. I’d be able to have a stable income while subversively sticking it to every “wot if it was a scholarship” or “my parents just worked really hard” psychopath I’d clashed with.

I decided to dip my toes into education via the aggressively unfashionable arena of teaching English as a second language. Admittedly, it’s a path most people associate with gap years and getting chlamydia off Australian backpackers. I remember a friend of a friend laying into my decision at a post-rave house party. It wasn’t out of malice rather a very middle-class person of colour diatribe to preach. Y’know, rail against the system, say things like ‘erasure of language’ and ‘diaspora’ while doing cocaine off dinner plates. Not long after that night, I decided to stop going out altogether and deleted my social media. The job search required warding off the ghosts of fifty-tweet long rants and forming opinions by myself.

My first job was at an FE college, teaching students from countries derailed by conflict which meant traditional education was just not a thing. So classroom instructions like “sit in a circle” became ten-minute long absurd comedies, as did handwriting and mouthing out letters of the alphabet. Every small victory, be it posting a parcel or asking for a bag at the supermarket, we’d celebrate in class like it was someone’s graduation day. It was the most useful I’ve felt in my life.

Inevitably, the classes met their financial kiss of death. Funding ran out and I was unemployed again. So I did stints at language academies, chaperoning Italians around Westminster and making up facts about Big Ben. I spent a strange few weeks in France attempting to teach four-year-olds with PowerPoint presentations, before finding myself crawling on the classroom floor doing hour-long sock puppet plays. There was also the intensive “course” for a group of wealthy Arab and Japanese businessmen about ‘power posing’ I was somehow put in charge of, despite never being a manager and having £7 in my bank account.

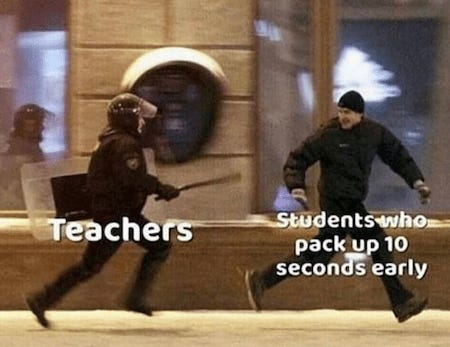

But then came the secondary schools. At that time I had somewhat of a vague, rose-tinted idea of working with teenagers; shaping young minds, getting people to ‘O Captain, My Captain!’ on the desks. I’d always enjoyed making guest appearances at schools; doing workshops and avoiding any chat of how to get “into” the media. I didn’t have the heart to tell them their best bet would be gritting their teeth while being maligned by entitled dickheads who hog all the opportunities.

So I skipped from school to school, depending on which councils had money left over to pay for the luxury of teaching assistants. Some were better experiences than others, but all of them had money problems and all of them required a certain level of masochism from the teachers. I remember my mouth inadvertently gaping open in a meeting after teachers were reminded about an unofficial “laundry club”. You were told to look out for warning signs of a family struggling —dirty shirt cuffs and backpacks falling apart— but once it was pointed out it was all you could see. This was a bus ride away from London’s ‘Billionaires Row’.

When another batch of council funding ran out, a recruiter got me a trial day at a pupil referral unit working as a literacy assistant. A pupil referral unit being a school for teenagers who have been taken out of mainstream education for a multitude of different reasons. The position paid a cool fifteen quid a day extra because of the risk of “maybe having a few chairs thrown at you.” I would love to say agreeing to this was an altruistic move, an opportunity for me to learn and grow. Actually, my parking ticket had run out and I just needed any income as soon as possible. So I started the next day.

I don’t know if any of you have experienced the thrill of being called a “fucking pussy’ole” on your first day at a job, but I have. I think everyone who goes into these kinds of lions dens clings onto a hope that they’re going to be that one teacher in someone’s life who inspires a student to do better. I naively thought: “well, I went to a state school, I know what TikTok is!” But, no. You will not be Michelle Pfeiffer in Dangerous Minds swinging a chair round to straddle it, you will just be a “fucking pussy’ole”.

As the weeks went on I got slightly better at suppressing the need to be liked and instead got stuck into the job. Language barriers, poverty, abuse, undiagnosed mental and developmental disorders — the layers of hardship multiplied by the speed and numbers of those falling through the cracks were outrageous. I was constantly biting my tongue, reminding myself the students with the foulest insults were often deflecting from their illiteracy, having been failed by the richest city in the UK. Striking the balance between being a parent figure and knowing that you are not the parent, and therefore can only do so much, proved to be the most brutal part. It eclipsed the job itself.

During my last week there, I caught a stray flailing fist in the back of the head breaking up a fight involving one of the most contentious students. I sat with him, fuming, as he waited for word on what his punishment was. I knew he liked drawing so we silently doodled on a miniature whiteboard together as I waited for him to apologise and he didn’t. I thawed a little after getting baited into talking about video games and realising I needed to be the grown-up rather than the one having a strop. The way he breathlessly spoke about Fortnite made me see the little boy in him. One that would, shortly, be out on his own in an ostensibly adult body and in a world that would certainly treat him like one.

On my final day, as I was gleefully handing out farewell bags of chocolate buttons knowing that I’d never have to set foot in that place again, the same student came to tell me I was “cool”. He walked with me to my car like a lost cat and laughed at the giant dent in my door from reversing into a wall. As I waved and drove away he gave me a big, sweet smile then stuck both middle fingers up at me. A perfect goodbye.

When I left the UK for a cushy teaching job I had two outcomes in mind. The first being to leave and never look back. The second being to travel, reset my batteries and return full of vim, full of measured and motivating anger. I was dead set on the former. Now that I find myself jobless yet again, stuck in this uncanny nightmare we’re all in, I’m back to that fork in the road.