Main Character Syndrome

Why is no one, I wondered, specifically considering ME and MY feelings?

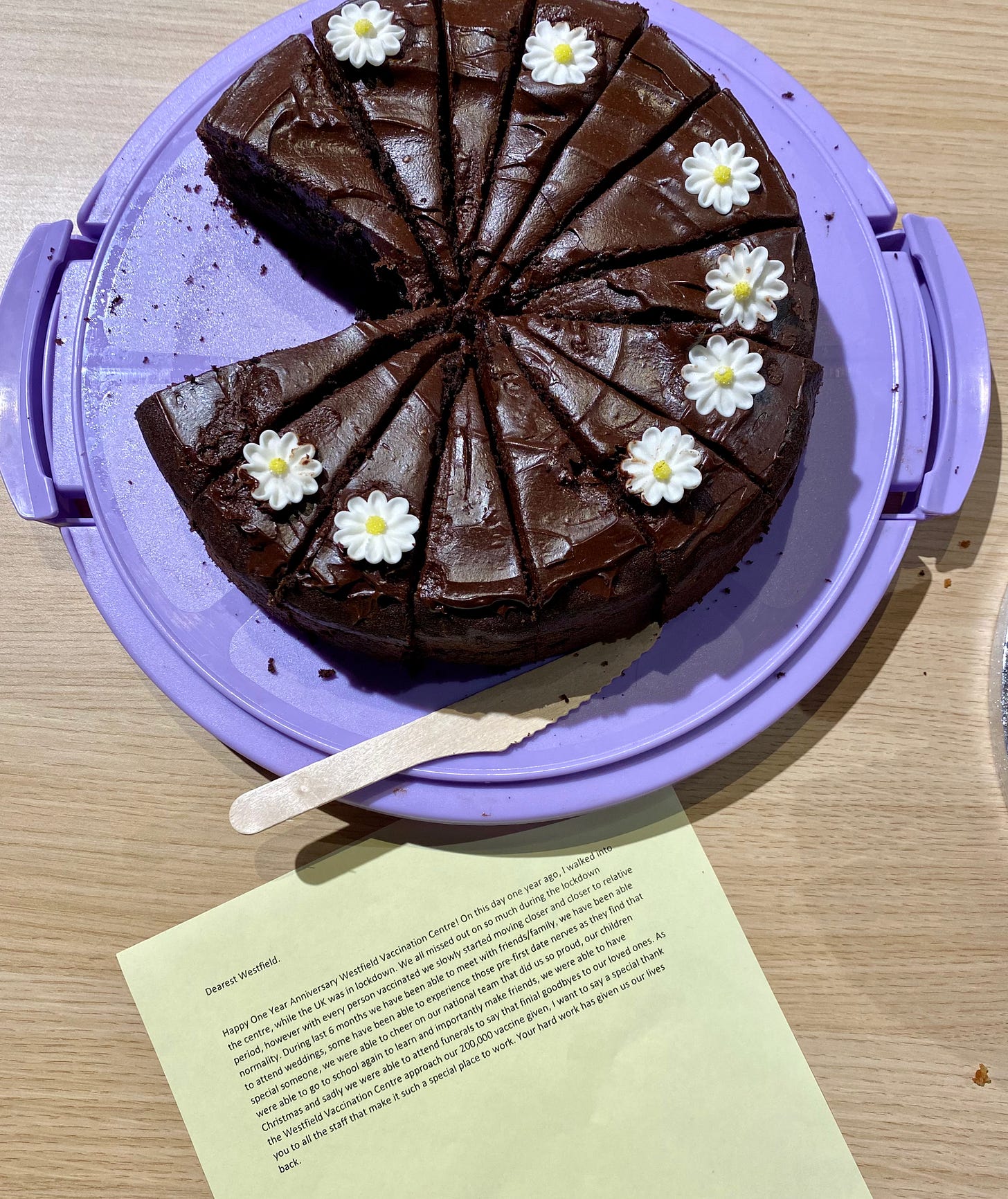

Many years from now, when we’re living in the mountains, fighting over the flesh of the last remaining radioactive goats for sustenance and all the rich people have moved to Mars, I will be sitting in an abandoned bar thinking about 2021. A wide-eyed child will gingerly approach me and ask, “Papa Jo?” (I don’t know why I’ve gone with Papa, but it feels right) “How many vaccinations did you give in The Pandemic, Papa Jo?”

I won’t turn to them. I’ll just take a long drag on the disposable vape I’ve found during my daily rubble dive and reply, “Couple thou’...what’s it to you, kid?”, my voice croaking as I inhale the excess haze sharply. “Wow, Papa Jo…what was it like then?”

I’ll turn my head only slightly this time to look them in the eye and say, “Fetch me another one of these and I’ll tell ya all about it.” The child will use what little is left of their strength to skip into the wasteland outside the bar to hunt for another vape. I’ll remain unmoved as, in my peripheral vision, a rogue Tesla cyborg blows the kid up into a red mist.

“A couple thousand,” I’ll repeat to myself, a single tear rolling down my cheek.

Last Spring, I took a call from my recruiter asking if I was still interested in training for the national vaccination programme. One part of me was like: wow, this is something that will never happen again in my lifetime. I could be a cog in a part of history…me, I, Jo, could be part of the first steps back to normality. Another much louder part of me was rapidly calculating how much time that’d buy me. Any pathos I’d assigned to working in healthcare had now shifted to digging my heels into gainful employment, cynically zoning in on the pandemic specific roles that had proliferated. Fit testing for respiratory protective equipment, taking blood for convalescent plasma trials, PCR testing — but the vaccination roll-out screamed six months full-time salary, at least.

I had not, however, given much thought to what an unusual position it was going to be; a kind of clinical-cum-retail role where the entire country was invited not because they were sick but because they didn’t want to be sick. At its heart has been a newly introduced legal mechanism, which acts as a kind of en masse prescription. It’s this that has enabled the whole thing to work at a scale there was nothing comparable in living memory to gauge it against, turning stadiums to museums into clinics. So the emphasis has been firmly on “mass” as well as “healthcare,” meaning an awkward balance between speed and intimacy.

After the starting gun had been fired for vaccinations to race the virus, we were given a short window of time to work as fast as is safe and hit targets set by a government whose primary goal was to gloss over earlier failings. This was to be offset by being the human element for a public coming out one of the most hallucinatory years imaginable. Naturally, there were times when there wasn’t any choice but to slow down for what felt like intensely private tears shed with both relief and grief over what had been lost. But for the most part, it meant plumbing adrenalin reserves only children's TV presenters maintain past their twenties.

The weather got warmer for each new cohort that was called forward and by summer there were flashes of unbridled madness; a vaccine administered nearly every three minutes to keep ahead of the queue. Management pinning signs up in the staff toilets reminding us to check our piss in case of PPE induced heat exhaustion. Patients fainting in the heatwave and learning the hard way that you should never attempt to break the fall of a six-foot rugby player. It was a frenetic blur.

On one especially busy day, there was someone I recognised but they didn’t recognise me. I’m talking about a level of familiarity where you’re aware of someone’s existence online, but you wouldn’t necessarily go up and chat to them IRL. Our encounter was swift but polite, and so nondescript. While I’d normally reserve my near-photographic recall for people that have been even the tiniest bit rude to me, I committed this encounter to memory because of what happened afterwards.

While idly flicking through Twitter on my break I was surprised when an entirely fictional — albeit positive, heartwarming, even — account of the appointment cropped up on my timeline. One of jolly Florence Nightingales and a drawn-out conversation about gratitude. I had become an unsuspecting bit player in someone else’s “everyone stood up and cheered” lie and I did not like it.

I mulled over confronting them privately but decided it’d be a dick move and let it go. Maybe I should feel guilty for robbing them of what should’ve been a joyous main character moment. But I’d also suspected a few other glaring didn’t-happens which, only through being privy to the more tedious workings of a news event, I know could physically not have taken place. Had the fictional thread been spun maliciously and the tale instead been: “woman body-slammed me to the floor and vaccinated me against my will” the best thing to do would’ve been a little more clear-cut.

I think it’s entirely human when processing huge, historical news events to cast ourselves as the central character, especially when we’re experiencing them both a little more existentially and from relative comfort. We foster proximity to the event that isn’t there, or in the case of the didn’t-happen just make shit up, to make us feel like we’re a part of something bigger, part of the action rather than an insignificant ant. I remember exactly, the well out of harm’s way suburban train I was waiting for when the London Underground was bombed. I remember the school detention we were taken out of when 9/11 played out on the TV. I think it’s this that sparks that initial inundation of support that happens in the aftermath of a tragedy.

But the pandemic has been surreal for two reasons. The first is that it’s not been a war or natural disaster in another country, rather something where everyone could ostensibly argue that they are indeed the protagonist. The second is that it arrived against a cultural backdrop where we’ve become so preoccupied with our ability to feel, that we believe what we feel matters more than reality. In wanting finite answers for complex crises, where more than one thing can be true at once and the villain of the story isn’t always clear, we’ve defaulted to our feelings because they can provide a clearer resolution.

You have to wonder if this social capital we’ve ascribed to being in a perpetual state of divine empathy, provides the ruse to be less so. It’s reached a point where you can take great pride in self-diagnosing as an empath, which I find strange because, by definition alone, is that not compassion without action? More often than not, it’s those with the luxury of time, money and vocabulary who could do more to help the next person that chooses instead to articulate why, actually, announcing they feel bad is enough.

I noticed this as the seasons changed and gratitude took a hard turn into palpably annoyed. At first, I put it down to the annual summer comedown of the UK, that national malaise that comes with putting the Havaianas away for another year and not being able to binge drink outside. Biblical floods interrupted the simulation of pre-pandemic living the sunshine brought. England had lost the Euros. People returning to the office were beginning to view their second dose as an irritant that made them late for meetings. The discourse had trudged on so long that the left and the right were overlapping, and becoming confused at each other’s presence. Most of all, I’d underestimated people's ability to get tired of a crisis.

I was somewhere off the A406, on the edge of the Tottenham IKEA when the dread began to take hold. In between applying for and getting this job, had been the minor obstacle of getting evicted. If your kink is humiliation, I’d recommend trying to get a tenancy during a pandemic when you’re both scraping around for work and trying to avoid public transport. My entirely rational solution for this was blowing a month’s pay on an old Yaris, then proceeding to bully my way to stability from one house-sit and one job contract to the next, commuting from whichever postcode I ended up in.

I was regretting this decision when I was, I thought, caught up in my third Insulate Britain protest in as many weeks, on my way back from a paediatric care training day that would mark the decline of any residual goodwill. The announcement of a third dose had just passed and failed to soften the ground for the much more contentious announcement of secondary-schoolers being offered the vaccine. The overarching reaction to which made it seem like the plan was to blow-dart teenagers with Pfizer.

As I was pushing my thumb into the throbbing behind my eyeball, I realised I was being literally edged forward by the bumper of the car behind me because I’d failed to creep forward the few feet we’d moved. Leg shaking from hammering the clutch, I decided I wasn’t in the best shape to square up to a mum in a Nissan Juke, so postponed the mission at the next slip road. I drove under what looked like a bedsheet clumsily unfurled off an overpass, emblazoned with the words “STOP KILLING OUR CHILDREN, SAY NO TO VACCINES” and, in the corner, a much smaller spray-painted addition of “Fuck off,” before hitting another wall of traffic.

It took me a minute to realise there was nobody superglued to the road ahead in protest, but I was boxed into a mile-long queue for a petrol station. The pumps had been hastily wrapped in hazard tape and a handwritten apology sign of ‘Sorry we’re out of diesel’ was doing nothing to dampen the anger. I think it was when someone laid on their horn for such a pointlessly long time, the futile primal scream of gridlocked traffic, that I began to seriously question whether I was having some kind of psychotic break.

On one side, were the lamentable spokespersons of those who think owning a Range Rover is a human right. They’d indiscriminately exploit the most emotional ‘gotchas’ of driving kids to school, phantom ambulances and taxiing sick relatives to hospital, getting to the jobs that feed their families. On the other side were those basking in their moral superiority as they jeered at people commuting to work from their uninterrupted remote jobs. They’d later use the same glee to reprimand people worried about unlivable energy bills. Now, let me be clear, I know which side was correct, which side was the one with foresight. But a suggestion made in jest that I should ‘get a bike’ to make a forty-mile round trip, from my precarious housing situation to my twelve-hour shifts made me want to go feral. Why is no one, I wondered, specifically considering ME and MY feelings?

I stopped short before I had the chance to join a petrolhead forum, but the more I tried to forcefully extricate myself from the outrage cycle, the harder I found it to avoid. I also had to have another quiet word with myself and remember that for a long time I used to indulge in hysterically getting my point across like my life depended on it. I knew how frighteningly easy the path to becoming a professional rent-a-gob is, in a climate where comment is king and framed as equivalent to reporting. Where being able to articulate a strong belief can make you an oracle on genome editing one day and the USSR the next.

Mercifully, work had been providing me with a crash course in the perils of unchallenged subjectivity. When asked for wild stories, I instinctually grandstand about the most hysterical incidents I can think of. A wellness guru, part of a stifled protest, craning to spit at staff but then ending up just kinda dribbling down herself and having to clumsily wipe the gob off her own face. The man who interrupted my break to let me know I was a government agent with Big Pharma blood on my hands, before asking where he could get a good iced coffee. My ASDA delivery driver goading me into trying to stick a teaspoon to his unvaccinated and therefore unmagnetised arm.

By way of having to offer continued care, even when I wanted to curl up into a ball and start screaming, you were forced to listen to the multitude of highly personal reasons they arrived at these beliefs. Their headline may have been that they cared so much about the wider public they were willing to hide razor blades in anti-vaccine leaflets, but the footnotes were always the same. A laundry list of feelings of disenfranchisement, distrust, fear, paranoia all borne out of personal experience and bolstered by easily disproved misinformation.

I realise this is not a groundbreaking revelation to have but I worry about our inclination to dismiss these as a disturbing minority. They may be the more ridiculous anecdotes but the conflation of facts with feelings was, I found, upsettingly common. It’s a rabbit hole we’re all much more susceptible to falling down than we think.

The ice coffee guy gave a nod of acknowledgement as I slunk into work late. He’d returned that morning to chant “YOU ARE PART OF A CLINICAL TRIAL” at the queue building outside. I mouthed ‘what the fuck’ to myself as I got closer, realising how far the crowd of people snaked beyond our now measly barriers.

The hot new variant, Omicron, had dropped and Boris had just announced that every adult would be offered a booster dose before the year was out. By just announced I mean hours earlier and by end of the year, I mean in the space of two weeks. Bearing in mind, for every single change in circumstance the legalese of the mass prescription had to be overhauled. So though the summer had smoothed the days out to as close to a military operation as possible, this felt like a pressure cooker.

The queue was so absurd that our centre at least was left weighing up the risks of working beyond capacity, pitting the likelihood of exhausted staff making mistakes against turning people away. Which would mean dispassionately culling the queue by who is statistically more likely to end up in intensive care if they caught COVID-19. Selfishly, I was OK with this because I was going to be inside, safe with my cotton wool balls and syringes, not out there with the baying general public. You may be thinking melodrama over one queue is misplaced, but I’d direct you to all the times a crowd of emotionally-charged people have not thought rationally.

Anyway, I lasted about fifteen minutes before I was sent outside.

I feel compelled to put a disclaimer here about how, predominantly, people were kind and patient. It’s just that’s never what you remember is it? As is the nature of my previously mentioned photographic recall, there’s another person I can bring to mind vividly. My confidence had been shaken as, right out the gates, a sweet old man announced I was ‘useless’ because I would not give him a box of staff lateral flow tests. But I’d regained my balance and was skating down the line when the next happened.

“Hello, can I ask for your age?” I asked cheerfully.

“Hey! I’m 27.”

“Do you have an appointment?”

“I don’t.”

“OK, do you have a condition that means you’re clinically vulnerable or do you live with someone who is clinically vulnerable?”

“No…I just saw that the booster was opened up to everyone.”

“I’m really sorry but as you can see we’re overwhelmed today and are prioritising by vulnerability. We'll be taking your age group in a few days…two days? You could try another centre, but we won’t be able to give your booster here today.”

“So why would you announce it?” he pressed, an accusatory stink now forming. I did a Scooby-Doo gulp, bamboozled by the use of ‘you’, desperately trying to remember the conflict resolution training and what I should do with my hands. Behind the back or get into an ‘I’m a little teapot’ stance?

“I’m sorry, but-”

“What difference does two days make!” he cut in.

“Yes…what difference does two days make?” I replied pointedly, before immediately regretting it.

“It’s just useless! I’ve come all this way. It’s SUCH bureaucratic…-ness,” he stumbled. “If people who bothered to turn up want it, doesn’t it make more sense to give it to them?!”

“I understand and I’m sorry,” I mumbled, “but…the bookings haven’t actually been opened up to your age group as of yet.”

“IT LITERALLY SAYS ON THE NEWS,” now pulling out his phone to show me the proof. I didn’t have the heart to ask him to scroll to the end of the article in front of everyone and read aloud what I’d just spent the last five minutes repeating.

“As you can see we’re overwhelmed right now and have to prioritise the most vulnerable. The bookings…” I began again, more firmly.

He looked up into the air incensed as I rolled out my Linus blanket script but I could see he was about to completely lose it in the face of this great injustice. Before I could continue, he added, “So you can’t see one more person who has made the effort to come here?” The ‘one’ was emphasised by his finger which I stared blankly at. He folded his arms, tote bag slowly slipping off his shoulder as he cocked his head impatiently. I could see what he was driving at; he was a good guy, he had dutifully turned up and wanted to do his part. Probably loudly boycotts Amazon, reprimands teenage girls for buying fast fashion and gives immigrant Uber drivers five stars if they behave in a way he deems fit.

But man, I thought, how annoying would it be if I started again with, “As you can see we’re overwhelmed.” Instead, what happened was I found myself reverting to this Christ-like serenity of being very still and quiet when I was, in fact, short-circuiting. I could be so immovably level-headed and explain the dilemma we were in, explain the boring mechanisms that’d made any of this possible in the first place, so he’d feel like a fool of his own volition. Or I could lose my job by using the tried and tested method of repeating verbatim everything he said in a stupid voice. Really, all I wanted to do was yell back, “WHY ARE YOU BEING MEAN TO ME, I’M TIRED?!”

Breaking our staring contest, he launched into an eloquent tirade that’d obviously been brewing in the queue of how incompetent we were. How I was personally destroying his Christmas and how nobody could fathom the trauma he’d face changing flights he’d booked. And I just stood there dumbfounded, blinking at him like a cow observing you from a dual carriageway.

“This is fucking disgusting,” he spat, pushing past. I watched him stamp off while muttering that I was a ‘prick’ before turning to the next person in the queue, making the bells on the reindeer antler headband I forgot I was wearing gently tinkle. A woman tightly scrunched her eyes with a smile above her mask, as if to reassure me that she was not going to do a repeat performance, and I was grateful.

When I went home, I laid on the bed for hours compulsively scrolling through the news, idling over stories about the booster queues, vox-pops on how poorly they’d been handled, how unduly long people had to wait. I could feel myself getting angrier, taking every individual complaint like it was a personal affront. And then I started spiralling about how uniquely shit everything was, how difficult and unfair everything felt. This must be the apocalypse, so it was a matter of time before we all started eating each other and having knife fights over petrol — why not just start now?

That, I began to realise, is the most harmful feeling of all. Not anger but apathy.

There’s this misnomer that we’re living through historic events. But Reddit tells me the pre-Bubonic Plague Middle Ages is probably where it’s at if you want a more sedate news cycle, which doesn’t seem preferable. I think what we’re actually living through is a time where irrefutable logic can be debated simply because someone can argue they feel the opposite. Where our ability to scrutinise the world in a helpful way is being clouded by crowning how we feel as individuals as more important.

I believe wholeheartedly that we are at our core compassionate. But clearly, a bunch of experts unsentimentally presenting facts available to them, in a rapidly evolving crisis and begging people to think critically is not enough by itself. Rather, there is a place for harnessing how we feel, it’s consistently fury and sadness that rouse us into action after all. But it must be tempered by reason. Everything may feel heavy, but there is always a reason to keep going, there is always something you can do even when you feel insignificant. It just probably won’t be the protagonist’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning victory lap you’re hoping for.