Ethel and the Army of Stray Cats

Ethel is a precious baby. Barely out of kittenhood she’s a stray that lives near my apartment. You walk along the river, through what was a pre-pandemic dogging spot for couples having affairs, and there she is. Lately, she’s been looking a little rotund and I anticipated the worst. My poor Ethel, getting railed by strangers in the night, wasn’t ready to raise kittens by a roadside. I’m bringing this little kitty the finest tuna in spring water, flecks of spit leaving my mouth as I yell at the male cats to stay away from her.

Long story short; Ethel has turned out to be a boy. The belly is from being fed by at least six other people in the neighbourhood. But I’d already started writing this analogy before I found out so you’re going to have to roll with it.

I’m now at an age where it’s not out of turn to ask if I plan on starting a family or have a special someone in my life. My friends are having babies and settling down with the loves of their lives. I, in contrast, am heavily invested in the small militia of stray cats I’m building. Right now, being loved by someone seems like such an alien concept that I’ve started to prepare myself for it passing me by. That's not intended as a “woe is me” cry for help rather I’m being pragmatic.

For as long as I’ve been dating I've looked for men who I shared one common hobby with. That hobby being: not liking me very much. Sometimes this manifested as a gradual disinterest and other times, the worst times, as violence. Plenty of people have offered unsolicited psychoanalysis on why this is; how I must’ve been abused as a child or had a puritanical upbringing. Neither of which is true but I understand they’d be the most convenient answers and people want neat explanations for things they find uncomfortable.

In my twenties, journalism turned out to be the perfect home for me to compound the unhealthy relationship I had with men. When editors first started to notice my writing I looked forward to the idea of a career mentor or perhaps, *gulp*, a father figure. I found lots of people in the industry took it upon themselves to take credit for finding me, throwing a crumb here and there, dropping my name in newspaper interviews. But — and I’m sorry for the arrogance — I was a better writer than every man who tried to mentor me then, I just had zero industry acumen. I found myself being trotted out to fancy meetings as some kind of sacred cow; drinking too much at business lunches, slagging off magazines and not knowing things on posh menus, and it thrilled people. I never reaped any of the opportunities on offer, though. I remember one editor introducing me as “full of piss and vinegar” but every time I was full of said piss and vinegar about getting paid or being credited, it became unpalatable.

Still, I made baby steps. If I looked outwardly successful then surely stability and respect would follow. When I started editing Noisey I took solace in the power trip of the title, even though my ideas were rarely listened to and my time was spent fiddling with HTML, not writing. I tried my best. Eventually, an Oxbridge grad and notorious greasy pole climber was hired above me, on more money and fewer days a week. It was humiliating.

However, outside of that office people assumed I was important and I got high off it. I was socialising almost exclusively with men in the music industry and enjoying feeling like King Shit as I looked down my nose at wild-eyed girls trying to get backstage. Despite me being the one pushing promiscuity into unholy new bounds I reasoned that I wasn’t a groupie. I was important, dammit! It's funny, of all the dumb shit you can do in your life your sexual history is the hardest slate to wipe clean, the one you're judged the most fiercely on.

Coupled with the lunacy of ecstasy making a comeback, I was privy to and sometimes on the receiving end of some truly degenerate behaviour. One moment that really stuck with me, however, wasn’t the most debauched but an experience where I wanted to say something and lost my voice. I was the only woman in a green room with a bunch of artists, relaxed and not tempering what they were saying, when a girl was shepherded in alone by security. Extremely dressed up and clearly intimidated she glanced at me, I think, hoping for some warmth. I glared back. The atmosphere changed immediately and we were marched out of the room as she was left with one of them. We locked eyes again as she looked back at me, the closing door eventually obscuring us from each other. A lamb to the slaughter. I got upset but couldn’t articulate exactly why and it annoyed everyone. I was souring the good mood.

I don’t know why that shocked me so much but it acted as the precursor to a heinous stretch of partying. A few weeks later, at the VICE 10 Year party, I remember strolling straight in with wraps of MDMA hidden on me in various nooks and crannies, ready to farm out to artists. It was a fun night and I was in high spirits until I heard someone I worked with announcing that I was a “great fuck”. I had that hypersalivation you get at the back of your mouth where you’re not sure if you’re going to vomit or burst into tears. So, naturally, I proceeded to spend the rest of the evening getting completely annihilated.

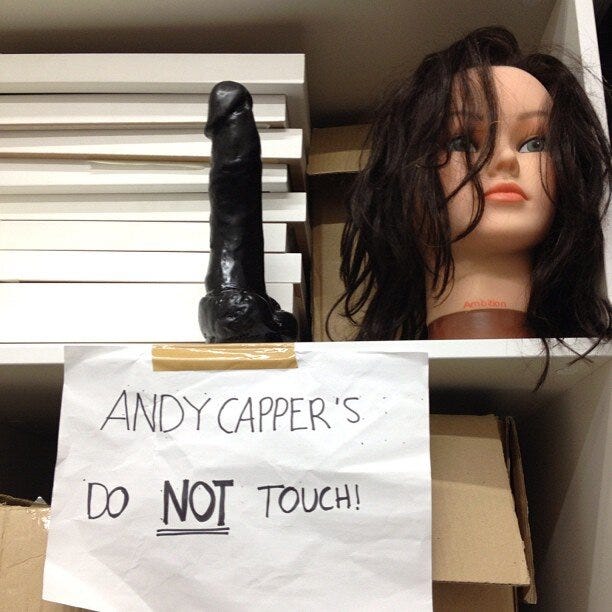

Once Noisey had become a total dead end, I gently threatened my bosses with a constructive dismissal case so I could move laterally into video production. It meant giving up the title of editor but I hoped I could get a fresh start. It was a shit-show, of course. A new arena to be undermined within. In their desperation, a female manager was drafted in to whip everything into shape. She was some big-shot director and, for a moment, I thought things might change.

She commissioned the last documentary I presented. There was footage where I’d started crying during filming. The shoot had been disturbing and I’d been a nightmare. The fear of becoming so burnt out that the bosses only had to knock you down with a feather was something I'd seen happen to women there before, but for some reason I thought I could survive it. It was uncomfortable to watch back and still is. When notes came in to cut it out of the edit because there’d been “too many female presenters crying on camera” I wanted to burn the building to the ground. It felt like: we will shit on you and shit on you and shit on you but please don’t cry it, it’s not good for our brand.

As the edit continued any pretence of friendliness between myself and our new feminist-saviour disappeared. I remember coming out of an edit suite, repeating her name, Alan Partridge style, waiting for her to turn around, but she was busy laughing at one of the bosses subpar jokes. Every time she coquettishly swung around in her chair, throwing her head back with giggles I fantasised about lunging over and tipping her out of the chair so her teeth would slam into the edge of the desk.

She recruited a conveyor belt of similarly hateful female freelancers, who got wasted at office parties and flirted with execs. Which I’m thankful for because it was like looking into a crystal ball of exactly what I didn’t want. I did not want to be the forty-year-old company lapdog, asking interns for cocaine after a long day of bullying.

Despite how much I disliked her I still ended up intimating how pained I was at being pushed out of my job. How I, and others, had been treated in the hope she might muster up some empathy. What I confided in her became part of the assortment of wrongdoings they hobbled together in my gross misconduct case. Making false allegations of sexual harassment, to be exact. And that’s when I knew she was just a cunt.

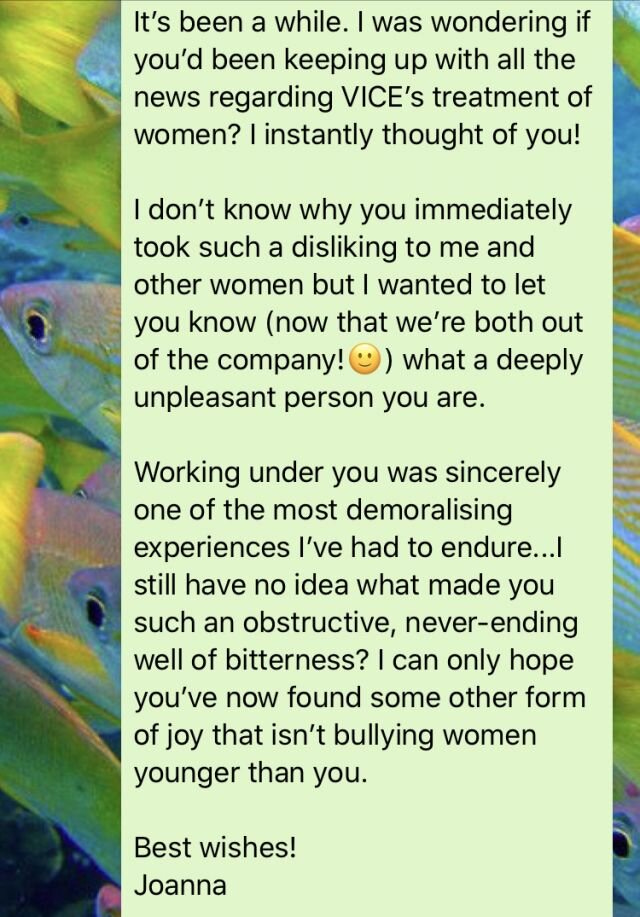

When the anger behind Me Too started to swell in a way that couldn't be ignored, I stayed up late every night talking to women I’d formerly been pitted against. We tussled with the prospect of an allegation being able to end a career. How much of ourselves should we give away to teach someone a lesson? It was another one of those bizarre news cycles where it’s lived through scrolling timelines and fervent private messages. A monumental social shift, where the anxiety grinds you down yet you’re only watching it play out on your phone.

I felt no satisfaction watching old bosses arm themselves with platitudes on how they were “taking time out to be with their family” as if the biological wonder of having children made them good people. The worst offenders were shuffled around into less high-profile positions or put on paid leave. The reporters sniffing around for more juicy stories stopped replying to messages. Only to be replaced by male writers hoping to find dirt on each other. If this was the great reckoning it was shite. On Christmas Eve, without warning, The New York Times exposé limped out and I thought “welp, that’s the only time my name will be in NYT!” What I was left with was a nagging pressure to perform trauma, like Jackanory storytime but for, y’know, assault.

In the past, I’d been guided not to say anything because the repercussions would not be worth the trouble. And I don’t just mean with VICE but with so many confusing and devastating interactions with men. Don’t speak up, don’t retaliate, don’t wear this, don’t be aggressive, don’t ruin a man’s life...he has a family for goodness sake! I have never felt scared to stand up for myself but I've always felt muzzled. To not have been brave when I wanted to be brave, to only say something once people were pulling up a seat to listen to the very worst memories being dredged up is a huge regret. But what can you do?

Nevertheless, I am enjoying these letters. I know I'm not going to get the Phoenix from the ashes moment I wanted and longing for retribution will only drive me mad. But in writing to you I feel like I’ve got my voice back.