Escaping Plato's Cave With a Nokia 3210

A wonderful thing about modern technology is you can go online at 3 am and drunk-book a therapy session for the next day. I was in the grips of yet another failed relationship, had no work coming in and had just moved back in with my mum. Why I thought dropping fifty quid on talking to a stranger for an hour was the solution, I’m not sure.

When I’d been in the process of getting fired I was pointedly asked to see the company therapist alongside a request for my medical records. The prospect of having the entirety of my medical history laid out to a tribunal and be painted as mentally incompetent was too much. Which was exactly what they intended. I’d had stints of CBT through my doctor, but still held a deep suspicion of anyone wanting to root around in your brain. And I’d always found something unnerving and self-satisfying about the ease at which people spoke about “their therapist”, like they were in a budget Woody Allen movie.

I was sacked shortly after I declined to see the therapist. After which I went full force into freelancing, accepting everything that came my way. I’d envisaged leaving in a blaze of glory and emerging with a ton of exciting projects. In reality, I was producing video in the day and writing through the night. The weekends were my allotted hysteria time, where I’d ritualistically watch Mad Men. Specifically, that episode where Freddy Rumsen pisses himself before a meeting, is fired and says to Don “who am I if I don’t walk into that office every day?” I was working so much that after ignoring a UTI as a minor inconvenience I ended up with a kidney infection that blindsided me.

It was during this lull that I’d started speaking to a reporter at the New York Times about my experience. I’d leaked documents, including my NDA, and was naively reassured that there’d be a positive outcome. When the article came out I had a huge outpouring of support and a large nosedive in work, which became self-fulfilling. I was paranoid that no matter my good intentions if I were an employer looking to be pragmatic, I’d rather go with the safe option I can trust than the nutter who sues their employer.

And so I sank.

By the time I had the first session with my therapist, I was ready to blow. I turned up hungover, smelling ripe and relieved to cry. And I fucking loved it. Which is why I was surprised when every time we met after that felt like hard work. I’d leave exhausted as if I’d been swimming laps and got angry at how much money I was spending. During the hour’s drive to her office, I’d arm myself with anecdotes only to get defensive when she asked why I was feeding her bullshit.

It was an expensive six months before I reached what people call a “breakthrough”. Something I expected would hit me with a choir of angels and miraculously bestow me with direction in life. Instead, I drove to the car wash, put Magic FM on at full volume and cried in the privacy of the soap suds.

In that particular session, we touched on all the things in recent years that had really got to me. Losing friends, losing relationships, VICE, Grenfell, evictions, assaults — none of which were new territory to our sessions. Then she asked why I chose to write around these. Why over the years I’d become a master manipulator, and obsessively write about myself through the prism of other people and other subjects.

After that, I decided to start a private journal. So if some parts of these letters feel like you’re reading my diary it’s because you are.

I know it’s a cliche to blame your parents for why you move mad but to understand why I have such a well of dramatic stories you need to know what an odd childhood I had. My therapist enjoyed using the allegory of Plato’s Cave to describe it: a tale about a group of people who live in a cave. When things moved outside the cave entrance, the fire they sat in front of would create big, scary shadows on the walls. The shadows were so frightening they refused to leave the cave, convinced the outside was full of evil. This is a convoluted way of saying “my parents were scared to let me leave the house.”

I am loathed to describe any part of my childhood as bad because my family loves me and has done so through some extremely stupid life choices. But when I describe how I grew up it sounds as if I was in history’s smallest cult.

Both being NHS nurses in high-stress positions, my parents worked strange hours to make ends meet, which meant even stranger hours for me, my brother and my sister. I have continued to be nocturnal well into adulthood. They'd experienced their own traumas, including as a couple, racism from strangers and family members. My older brother was referred to as a monkey and my grandmother once nicknamed my mother the yellow peril.

Addiction was always a spectre, as were periods of mania but it was an extreme anxiety that ruled the roost.

By the time it came to my sister and me there was an unspoken rule that we just do not leave the house. Not to play with other children, not to walk further than the postbox, not to answer the door or the phone, not to do after school activities and, by no means, no socialising outside of the house as a family. We had an accepted set of friends' we visited and sleepovers meant weeks of negotiation.

My dad especially was terrified of what would happen if my sister and I were let loose into the world. The constant level of potential catastrophe they operated at was hard not to inherit. I didn’t know any of this was unusual, of course, and though I got aches of wanting to be “normal” I was quite happy to retreat into reading and drawing. One time, when a plumber was working in the house he was horrified to bump into me playing in total silence like a haunted doll.

But then came my teenage years and the Holy Trinity: MSN Mesenger, my own mobile phone and the arrival of my national insurance number. I was 15 when I got a job at TK Maxx and as soon as I started was bullied relentlessly by a group of older girls. A hardship that seemed to miss me at my school. Part of the appeal of the cult was a relaxed attitude to even going to school...as long as I got decent grades.

I quit in the middle of my shift one day having squirted superglue all over one of the girl’s clothes in her locker. But the parting paycheque was enough for my first phone. I quickly graduated to a Nokia 3210 with The Exorcism theme as my ringtone, having reached the retail heights of a weekend job at Quality Seconds. If you’ve never heard of QS, it was a shop that sold both pleather mini skirts for nine-year-olds and cardigans for women who’d truly given up on life. I remember my face flushing when a busload of people from my school idled outside the shop just as I was grappling with the floor buffer. I went hot with embarrassment but little did they know I was using my pay to fund a parallel life.

By 16, I’d become so skilled at both lying to my parents and using MSN and texts to coordinate covering said lies, that as long as I returned home in one piece I could do whatever I wanted. I went to Carnival, I went on nighttime drives around Ally Pally, I partied at garage raves with adults. Including men who studiously ignored my train track braces and the fact I’d sewn padded inserts into my shoplifted boob tubes. So long as I had money and a phone I had autonomy.

I carried on having this wild, second life right up until I was fired (look at me bringing you full circle!) It was then that I had to be blisteringly honest with my parents because I wanted to be let back into Plato’s Cave. I retreated back to their support as I was battered by the company’s lawyers on everything from my drinking, my buying drugs for artists we worked with, my casual use of slurs and my generally being a shitty person. Out of the context of the culture of VICE I sounded like a monster and, tbh, I was. Then came the New York Times story on sexual harassment and some uncomfortable truths for my mum and dad. It was one after the other of the very things they’d tried to protect their children from.

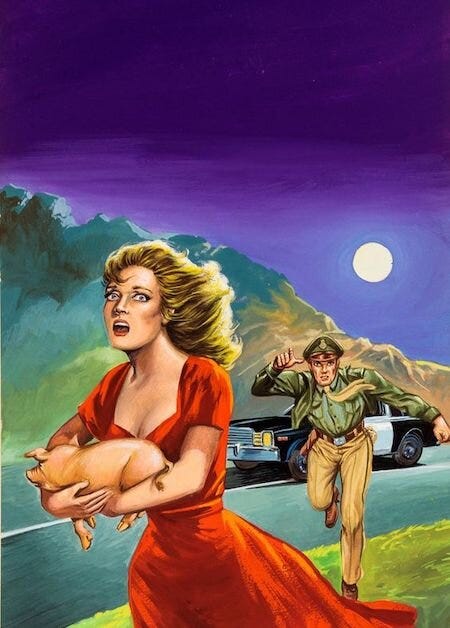

In that breakthrough session, my therapist described that abrupt breakdown of the barrier between my two different lives as like being an unsocialised puppy. Or, in this case, the puppy who’d escaped Plato’s Cave. I was never a child who felt like they lacked love but when unleashed into the “real world” I went off the rails. Without being exposed to failures, conflicts and nurturing friendships I navigated them as an emotionally-dumb adult. Unaccustomed to the fact that the universe is random and not personally vindictive, I still get shocked beyond reasonable reaction at how unfair life can be and how awful people are.

It’s a flavour of psychotic idealism I’ve had to put long hours into controlling. A mindset that makes it hard to escape cycles like: “I didn’t do anything wrong why am I being fired!” or “I like you, why don’t you like me back!” and the classic “Hey, why are these incredibly rich and privileged people being such cunts?” The same ‘I’m right, you’re wrong’ pigheadedness in which I can see myself leaving my body as I tear into someone’s jugular for not having exactly the same views as me.

One day I’d like to bottle it all into something more useful. But now is not the time.

Since I moved to Costa Rica I’ve had lots of people ask me: why here? I like to feed them some line about learning Spanish and going to the beach but I came here because Costa Rica is a country that shuns drama. I’d toyed with other destinations much livelier and with identities much more in your face but there is something endearingly placid about life here. Often amazingly frustrating, yes, but everything here invites you to slow down and take stock of what you need versus what you want.

In this limbo of being abroad but in lockdown, I’ve had time to appreciate what was fractured and is now a repaired family relationship. And though I realise I’m not the first special little human to live in a different country, it does mean being fired is no longer the most significant thing to happen in my life.